A

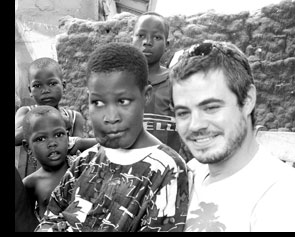

year ago I left the streets of New York City for the shores of West Africa

to serve as a volunteer photojournalist onboard a hospital ship. I’d

made my living for years in the big apple promoting top nightclubs and

fashion events, for the most part living selfishly, thoughtlessly. Unhappy, A

year ago I left the streets of New York City for the shores of West Africa

to serve as a volunteer photojournalist onboard a hospital ship. I’d

made my living for years in the big apple promoting top nightclubs and

fashion events, for the most part living selfishly, thoughtlessly. Unhappy,

I needed a change in my life.

The humanitarian organization I joined was called Mercy Ships. They operate

hospital ships in the world’s poorest nations. Surgery ships. They’d

been doing it for more than 25 years, producing astonishing results. Top

doctors and surgeons from all over the world left their practices and

fancy lives to operate for free on thousands who had no access to medical

care. The organization was full of remarkable people. The chief medical

officer was a surgeon who left Los Angeles to volunteer for two weeks

–19 years ago. He never went back.

I was offered the position of ship photojournalist, and immediately traveled

to Africa. At first, being the Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s

court felt strange. I traded my spacious midtown loft for a 150-square-foot

cabin with bunk beds, roommates and cockroaches. Fancy restaurants were

replaced by a ship's mess hall feeding 400 Army style. A prince in New

York, now I was living in community with 350 others. I felt like a pauper.

But once off the ship, I realized how good I really had it. In new surroundings,

I was utterly astonished at the poverty that came into focus through my

camera lenses. Often through tears, I documented life and human suffering

I’d thought unimaginable. In West Africa, I was a prince again.

A king, in fact. A man with a bed and running water and food in my st

omach three times again.

But once off the ship, I realized how good I really had it. In new surroundings,

I was utterly astonished at the poverty that came into focus through my

camera lenses. Often through tears, I documented life and human suffering

I’d thought unimaginable. In West Africa, I was a prince again.

A king, in fact. A man with a bed and running water and food in my st

omach three times again.

In Benin, and then Liberia – a country with no public electricity,

running water or sewage – I put a face to the world’s 1.2

billion living in poverty. Those living on less than $365 a year –

money I used to spend on a bottle of Grey Goose vodka. Before tip.

Our medical staff would hold patient intake “screenings” and

thousands would wait in line to be see n, many afflicted with deformities

even Clive Barker hadn’t thought of. Enormous, suffocating tumors

– cleft lips, faces eaten by bacteria. I learned these medical conditions

also existed here in the west, but were taken care of – never allowed

to progress. The amount of blind people with no access to the 20 minute

cataract surgery that could restore their sight – all part of this

new world.

Over the next eight months, I met patients who taught me the meaning of

courage. Slowly suffocating to death for years and yet pressing on, praying,

hoping, surviving. Some of their stories

follow. It has been an honor to photograph them. It has been an honor

to know them.

Over the next eight months, I met patients who taught me the meaning of

courage. Slowly suffocating to death for years and yet pressing on, praying,

hoping, surviving. Some of their stories

follow. It has been an honor to photograph them. It has been an honor

to know them.

Mercy.

For me, mercy is practical. Sometimes easy, sometimes inconvenient,

always necessary. It is the ability to use one’s position of influence,

relative wealth and power to affect lives for the better. Mercy is singular

and achievable.

There’s a biblical parable about a man beaten near death by robbers.

Stripped naked, lying roadside – people pass him by, but one man

stops. He picks him up and bandages his wounds. He puts him on his horse

and walks alongside until they reach an inn. Checks him in and throws

down his amex. “Whatever he needs until he gets better.” Because

he could.

Shakespeare says mercy is twice blessed. That it blesses those who give

and those who receive. I know this much is true.

Please explore their stories

here

–Scott Harrison

|